It Turns Out, My 10-Year-Old Was Ready for Biochemistry: A Review of the Innovative Biochemistry Literacy for Kids Online Program

Soon after Covid-19 entered our collective vocabulary, I decided my little homeschool would devote 2020 to a more rigorous study of science. Covid-19 held a mirror up to our society, showing us how many Americans don’t understand and don’t trust science, and I wanted to be part of the solution by helping educate the next generation. I sought video lessons, bought a plant cell model, signed my son up for an Outschool class on the Periodic Table, and expedited our march through some science textbooks. Then, in June, I happened upon an online demonstration of a program that, however improbably, sought to equip elementary-age children with literacy in biochemistry. This program, Biochemistry Literacy for Kids, should be on the radar of every homeschooling parent.

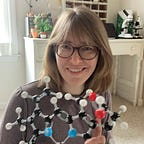

Archived on the program’s website is an impressive array of videos made by children my son’s age and younger. These kids display the molecules they have constructed from their plastic Molymod molecule-building sets and describe and teach things like electron orbitals and covalent bonds and DNA base pairs. One five-year-old draws all twenty amino acids — from memory. Those videos give credible evidence to the claim on the website that this program provides “College learning for elementary students.” The price for the program — about $100 for full access to 24 recorded lessons, handouts, and instructions for using a digital molecule-building software program called Pymol (and another $45 for a custom Molymod set) — seemed like a very good deal. As I discovered after registering, program creator Daniel Fried invites all newly registered learners to meet him at one of his regular introductions on Zoom. He was easy to talk to, enthusiastic about his program, accessible, and knowledgeable. Could I have found the perfect program?

I called my friend Melissa. She homeschools near Charlotte, and her two kids are 8.5 and 10. I pitched the program to her. At first she seemed hesitant. “Biochemistry? They’re just in the third and fifth grade!” She admitted having largely neglected science in her own homeschooling and feared her kids wouldn’t be ready for the program. I suggested our kids try it together, and I promised to give her two some introductory lessons to get them ready. Her kids, my kid, and I started meeting up every week on Zoom to go over Dr. Fried’s lessons. I provided some supplementary material, but mostly just followed Dr. Fried’s program. Within three weeks, these kids were logging onto our sessions absolutely on fire about the material they were learning. They were gamely drawing their atoms with the proper number of protons and pairing up the electrons on the proper orbitals, and soon progressed to molecule diagrams, from Lewis dot diagrams to ball-and-stick models, to stereochemistry perspective drawings. They didn’t learn these terms. They just knew they were having fun and growing confident, empowered and energized by the molecular world that was becoming clear to them. Ask any of them to describe the mechanism by which oxygen is carried by red blood cells through the body. Ask them how the chemical structure of the graphite that makes pencils work. Ask them to explain how the bonds in plastic make this non-biodegradable material almost impossible to break down. Ask them how fruit gets its smell. They’ll tell you.

By Halloween, Melissa’s daughter chose to dress up as a biochemist, and, outfitted in a white lab coat, she carried around the unwieldy molecule structure of a phenylalanine amino acid as she trick-or-treated. For his birthday, my son asked only for more Molymod sets so that he could build more complicated molecules. I was giddy watching these kids get so excited about the subject matter. This was a path made possible by homeschooling, but the medium was the program.

When I was my son’s age, at an Asheville, North Carolina public school, my fifth grade science curriculum involved memorizing definitions from a dry textbook in preparation for regular chapter tests and a memorable visit to the (now defunct) local children’s science education center, “The Health Adventure,” where we learned about hygiene and puberty. Now, as director of my son’s education, I have the choice of which formal science curriculum — if any — I want to use. And I feel so grateful I found Dr. Fried’s program. I wish it had existed for me, but, as I’ve learned, it’s never too late.

Meeting the Program’s Creator

In a time when STEM is so popular, but when robotics and coding get outsized attention, how did this biochemistry program pitched at elementary-age children come to be? How did Daniel Fried create his little start-up? I am a fan of the NPR show “How I Built This” and the interviews that show features with entrepreneurs, so I asked to interview him to learn more about his program and his story.

First, he told me about the magic he sees in a subject I had once thought reserved for pre-med students who had to pay their dues before they could practice medicine. “Biochemistry is just nature at high resolution,” Dr. Fried said. “If you think a walk in the woods is beautiful or magical, you will think the same about traveling into the 3D structure of a protein. Biomolecules not only are beautiful, symmetrical, chaotic, and exotic, but they also make up everything in the living world. Everything that is alive is biochemistry — we are biochemistry.”

We are, he proclaimed, “the first generation to have the privilege of understanding how living matter works.” However, he warned, “standard education has not yet realized that it should be bringing this knowledge to everyone.” Daniel Fried had the bold, radical notion that biochemistry “is one of the very first subjects we should be teaching to our kids.” Before the pandemic, I might not have agreed with him, but now I realize he’s right.

At the same time that I was getting acquainted with this curriculum, I was watching one close friend succumb to the diminishment of Covid-19 longhauldom, seeing the owners of some of my favorite local stores and restaurants strong armed by the virus into early retirements, and hearing doctors plead with people to heed the virus. Now, here was Dr. Fried making the compelling argument that kids should be learning to read the molecular world alongside learning reading, writing, and arithmetic. It’s not too hard to imagine what a different landscape we might be seeing before us if the American public had the kind of facility with the language of molecules he thinks important for all children. Imagine if everyone could understand electron bonds and “spike proteins,” and messenger RNA, and cell penetration. If we as a society had chosen to open up the beauty and magic of biochemistry to children, would we be in a different place right now? If Dr. Fried is successful, the next generation could have that literacy.

The Genesis of the Program

As a boy, Daniel Fried was a strong student, but a slow reader, and was frustrated by an educational system that wanted him to memorize answers to test questions without caring if he understood the reasons behind those right answers. He had been raised by free-thinking educator-parents who had encouraged him to imagine better practices in education. His earliest memory is of the construction smell from the innovative, Montessori-style preschool his parents had built on their property in upstate New York. He looks back on that memory as an early and lasting lesson his parents gave him: that anyone can create their own school. His mother taught thousands of hours of teacher professional development classes that prompted her to question the norms of what kids could do. She provided gifted enrichment at Daniel’s elementary school, and, in their dinner-table conversations, he grew up hearing both parents talk about learning, pedagogy, and school politics. Consequently, he matriculated through the school system with an unusual meta-cognitive understanding of teaching practices and learning processes. He remembers really wanting to learn high school chemistry, but when it didn’t click, he abandoned his original goal of majoring in one of the sciences in college.

In what would turn out to be an unlikely turning point in the development of his novel science teaching program years later, Daniel Fried majored in music at Temple University and became involved with something called Gordon Music Learning Theory. He got an internship teaching at a special early childhood learning center in Center City Philadelphia using this methodology, which proposes that students learn music from an extremely early age and directs that they be given rich experiences in modal music and in music with meters uncommon in popular music. “The idea,” he explained, “is to give students a much richer music learning environment than they typically get from hearing nursery rhymes or even traditional classical music.” Children trained in this method are supposed to develop the ability to “audiate,” which is basically the ability to read music and “think its sound” in your head (as opposed to traditional music learning, which involves reading music with the intention of just pressing the correct buttons or keys on the instrument). Gordon’s vision — that general music literacy would be so high that you might find people on a long airplane flight reading a symphony’s score as they would the newspaper — would eventually translate in Daniel’s mind into a vision for science education. When he taught the Gordon method to young children, he garnered such intriguing musical responses that he then replayed the traditional sciences classes he’d taken in school and considered how they could have been retooled to be much more effective. The music world, he noticed, puts a greater emphasis on high-level achievement at an early age, and, therefore, it’s not surprising to see young kids performing technical pieces, or even playing as soloists in front of an orchestra. “Why,” he asked, “does music expect so much out of kids, but science expects so little?”

Daniel Fried thankfully did return to science. He transferred from Temple University to SUNY-Binghamton and earned his Bachelor’s in Biochemistry. He applied into graduate programs and was accepted into Yale’s Ph.D. program in chemistry. The further he delved in, the more convinced he was that the way biochemistry gets taught sucks most of the life out of it. When he said that, I thought back to the premed friends I had at Wake Forest University, where I was an undergrad, and how they described the drudgery of organic chemistry, a dreaded, required, gateway course necessary to advance in science. It sounded grueling. Having approached graduate-level chemistry with a background in the arts, however, Fried dared to imagine a different way.

In childhood, Daniel had a family friend in childhood, Billy Hutcheon, who was a gifted visual artist-prodigy with a house popping with pieces he had made — from hyper-realistic portraits to psychedelic abstracts. Hutcheon volunteered to train young Daniel using Betty Edwards’s “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” technique (do you know that book?) to really encourage a student to see what they are drawing, and, which has proven that, after just a few hours of instruction, people can improve their technical drawing accuracy. So, as an adult, Fried could draw on these lessons and those of his years pursuing a music degree as he reimagined what a biochemistry course could look like.

At Yale, Fried worked hard on his courses and research while quietly mapping out how these high-level concepts could be taught in an engaging way to younger people. In his spare time, he worked out how he could create what he calls a “Betty Edwards version of Biochemistry” with a pedagogy informed by his musical upbringing. Eager to see how his idea could work in practice, he began offering experimental art and science classes for children of Yale faculty: the genesis of what would become Biochemistry Literacy for Kids. His ideas resonated with children. He started to shop his idea around with his professors and to investigate how to bring his ideas to the greater public.

By most measures, Biochemistry Literacy for Kids deserves national funding so that it could grow in scope and outreach — and Dr. Fried has sought funding through these traditional routes. However, as he found, the fact that his curriculum isn’t tied to science benchmarks outlined in the national Common Core curriculum — because he believes that children are capable of much, much more than the Common Core does — traditional funding sources have shied away from funding his program. Dr. Fried has more faith in children’s ability than do the gatekeepers of national standards. As his program began to be discovered by the homeschooling community this summer, however, Dr. Fried found the teacher-parents who shared his confidence in children’s abilities.

Now My Kid Thinks of Himself as a Biochemist

After learning more about Fried and his program, and after beginning it with my friend’s kids and my own, I was convinced the program could be transformational not just for my child, but for others in my community. I live in the Chapel Hill area of North Carolina, where, with nearby Durham and Hillsborough, there is a thriving secular homeschool community. I asked Dr. Fried if he would offer an introduction on Zoom to his program for families in this community. He agreed, and after his presentation, I recruited eight other families to engage Dr. Fried for a weekly private class online. Each family would follow the course, one lesson per week, and meet on Fridays to ask questions, take their knowledge to the next level, and get further enrichment. Dr. Fried’s computer is jam-packed with molecule diagrams, lessons, powerpoints, examples, and all kinds of material he nimbly draws from to follow kids’ interests. These classes had the rigor and intellectual stimulation of a college-class with the intimacy of a small Zoom call.

Our group was, it turns out, his first online class of homeschoolers, and the class was wildly successful. Other parents in the group shared with me how astounded they were by how quickly their kids were lapping their parents in knowledge and confidence. It was obvious that Dr. Fried was tapping into a part of their brains that was ready for this material. Even as the course exceeded my expectations, so, too, did it exceed Dr. Fried’s. He soon realized that even his lofty expectations about what kids were capable of absorbing had been not sufficiently ambitious. Time and again, the kids prove that their brains are flexible and their minds wide open, which Dr. Fried honors with his belief in them and their ability, and their enthusiasm reveals the fact that their imaginations are receptive to the magic of biochemistry, which Dr. Fried brings to life. Just as importantly, kids this age are still blessedly unaware that the world believes that biochemistry is too hard.

“It’s important to never underestimate kids.”

As Dr. Fried reflects, “My students are constantly exceeding my expectations, and they have taught me that I’mthe only limitation on their learning. If there is a very high-level lesson that I want to create, it’s up to me to find the way to reach them, make it fun, and make it meaningful.” As a homeschool mom, I find that he’s speaking my language. He continues: “It’s easy to say that kids of a certain age aren’t ‘ready’ for something, but in teaching thousands of kids over the past ten years, I almost never find this. If anything, I’m underestimating their potential and desire to learn. And if someone who runs a project that ‘brings college learning to the elementary level’ sometimes underestimates kids, what must be happening in standard education?”

Show me an example of you underestimating the kids, I asked. He pointed to one skill he’d always resisted teaching: electron pushing. I hadn’t heard of it. It’s a concept taught in college organic chemistry where you draw arrows on a molecular diagram to show how bonds form and break during a chemical reaction. It’s like identifying the very mechanism by which chemicals change, and when you learn it, it’s like a veil being pulled away from your eyes. Dr. Fried says he had tried teaching electron pushing before without success, but recently he challenged himself to use an even more sophisticated and visual approach.

“After just a few minutes, the kids were drawing the arrows correctly and explaining what they meant in a way that I’d expect of a good college student!” he reports.

In taking Dr. Fried’s recorded and private classes alongside my son, this is a refrain I’ve heard a number of times: that the kids readily soak up knowledge and skills that he expects from his college students, and young kids are often asking the kinds of questions that he didn’t encounter until graduate school. “I think kids can learn virtually anything,” Dr. Fried concluded, “and it’s my job to figure out how to do teach it.”

He points to his recent success in teaching electron pushing as the incentive he’s needed to begin designing additional lessons about how enzymes work, how materials are synthesized, and how biomolecules are actually made.

“It’s important to never underestimate kids. They are designed for learning — much more than adults — but it’s up to us to figure out how to reach them.”

It’s up to us, indeed.

The success of the private class my group took with Dr. Fried stuns everyone who hears about it. It’s like the pandemic hit, and, BOOM! My kid suddenly sounds like he has been taking an enchanted Hogwarts-esque train to an MCAT prep school. As I write this review, it’s Christmas week, and my kid is in the corner of the room building the skeletal structure of DNA with his sets of red oxygen atoms, black carbon atoms, white hydrogen atoms, blue nitrogen atoms, and purple phosphorous atoms and bendy plastic bonds, which he’ll tell you each stand for a “lone pair of electrons.” He’s chosen to build a thymine base pair to connect the strands. He’s still a kid. He imagines elaborate battles between his stuffed animals, needs to be reminded to brush his teeth each morning, and loves to climb trees and ride his bike, but tonight this is his chosen activity. And I owe it all to the program created by Dr. Fried and his live online enrichment classes, which have encouraged my son and the kids in his group to embrace their curiosity about how nature works on the molecular level.

December 2020